Social Curating and its pubblic

The most important question is, “in which precise moment curating declares its function

as being social?”

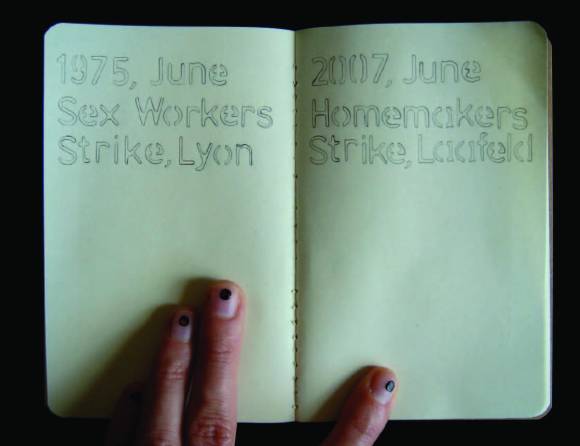

Sex Workers vs. Homemakers, a project by Elke Auer, Eva Egermann, Esther Straganz and Julia Wieger (Vienna, 2007), presented in the exhibition Toposcapes, curated by Marina Grzinic and Walter Seidl, Pavel House, Laafeld, Austria, 2007.

We have to address social curating’s condition of appearance, how and why it emerges at a specific conjuncture of our time. This has to be re-formulated taking into consideration the over-privatization of the institution of contemporary art today and the incommensurate commercialization of all the big curatorial projects — from Documenta to Biennales — that works hand in hand with a formation of monopolized curatorial groups and quasi-elite bodies of control and management of the practice and theory of curating.

How to proceed? Just to map different curatorial concepts binding them to their particular social conditions is obviously not enough. We have to “grab” curating in an almost Althusserian fashion, and ask for the history of curating to be seen “differentially.” Something akin to a “potential history”, that is developed by Ariella Azoulay against the background of Jewish and Palestinian co-existence, asking for the development of a curatorial project that she calls an “exhibition on paper.”

At stake here is not a division (that was never a case) between on one side of curating, the so-called curatorial elite of big curatorial events, and on the other the plebs of curating (hundreds of small important projects, curatorial struggles dispersed here and there on the globe). This division can be reformulated as the “form” of curating, that traces transformations within the discipline of curating (so to say producing almost an epistemological break), and on the other side the “content” that is termed as the politics, or better yet, the place of ideological struggles within curating. But I will argue we have ideology on both sides. On one side it is the logic of the production of forms of curating and on the other the “bothering” politics of curating that is seen as being directly ideological. In fact, curating was already from its very “beginning” not divided in two poles but “overdetermined” in a double way.

To state therefore that curating is ideological is not enough. The problem is that we never work with two histories when talking about curating. Let’s say one side will be the sequences of powerful history of “epistemological breaks” and on the other the “more” ideological (“problematic”) positions within the curatorial world. A case at stake here is the Documenta exhibition and what was announced as (post) dOCUMENTA(13), which took place in August 2012 at The Banff Center, Canada. This post-curatorial event is a cynical endeavor if we are to take seriously the fact that it is termed by the organizers as a “visual arts residency” with the title “The Retreat: A Position of dOCUMENTA(13).

What is important is to understand that the ideological is fully present on both sides, on the side of the form and on the content. Even more so in global capitalism, the ideological is no longer functioning on the side of the “content” of curating, on the contrary, the ideological is attached directly to the form, so that the process forming “the knowledge” of curating is now presented as “social” (social curating). While the other side, the political or ideological part of curating, presents itself as completely empty.

While we are problematizing the social as ideological we have in fact no content at all or better to say we have a post-ideological setting that is empty; the form is on the other side presented as an extra-ideological form of knowledge that is fully “social.”

In short, “social curating” has to be seen as a regime of curating that appears precisely in the moment where there is no trace of any social concern, but on the contrary the social hides the conditions and constraints of an invigorated global capitalist overexploitative conjuncture.

To proceed and offer a possibility to think of curating today as a pertinent political discipline, I will make reference to Achille Mbembe and Sara Ahmed, amongst others. They state that what is at the core of the social and political conjuncture of our time — is racism. Sara Ahmed argues that today it is possible to articulate political art only as an ongoing difficulty of speaking about racism and as well as queer of color activism.

Mbembe says that racial profiling have become commonplace, and deportation camps have been created for undesirables in the context of the EU. This is going on to such an extent that today one of the major characteristics of the nation-states in the EU is not them being nation-states but racial-states, as elaborated by Ann Laura Stoler.

Mbembe is talking about France though we will take this as features of the EU in general or as they like to call themselves “of the former West” in particular. He argues that we have a paradoxical situation as the idea of republic in the European Union are those of the “colonial republic”, and “humanity” then is nothing more than a colonial humanity. This could easily become emblematic for social curating as well. Therefore, let’s talk about the social, but again via Mbembe, if we want to talk about the social question of curating then we have to talk about a racial question.

Reflecting on social questions is therefore possible only situating curating in a wider context. In their article “The matrix of Curating”, Efrat Shalem & Yanai Toister state that the act of curating can be conceived as a model in which life and reality arrange themselves around curatorial models.

Because of this complexity, curating is presented as a matrix connecting reality and life. This gives us a possibility to connect curating with a “colonial matrix of power”, coined in the 1990s by the Peruvian sociologist Aníbal Quijano7. He conceptualized

the neoliberal world of capitalism as an entanglement of different hierarchies that works around the axes of sexual, political, epistemic, economic, linguistic and racial forms of domination and exploitation. This matrix, according to Quijano affects all dimensions of social existence such as sexuality, authority, subjectivity and labor. At the center of the matrix is the viewpoint of how race and racism become the organizing principle of all the social, political, and economical structures of the capitalist regime. Therefore what is necessary is decolonization. Chandra Talpade Mohanty, argues it is necessary to contest the exploitation by neocolonial global capitalism, with the elaboration of antiracist and decolonization pedagogy.

I want to present a curatorial project that reflects what was briefly elaborated. The exhibition, Toposcapes: Interventions into Socio-cultural and Political Spaces, that Walter Seidl and I co-curated in 2007 for Pavel House (Pavlova hiša).

Among the invited positions in the exhibition was The Research Group for Black Austrian History and Presence (Vienna), consisting of Araba Evelyn Johnston-Arthur, Belinda Kazeem and Njideka Stephanie Iroh. The participants in the exhibition produced a work that precisely captured the political and social space around Pavel House and the possibility of what I will call the “strategy of decolonization of Austrian social and political space”. The Research Group for Black Austrian History and Presence displayed a gigantic banner in Slovene and German language placed on the roof of Pavel House and visible while walking or driving. On it we could read ZAVZEMAMO PROSTOR/WIR GREIFEN RAUM (or in English WE ARE CLAIMING SPACE).

05 Issue # 18/13 social curating and its public: curators from eastern europe report on their practises

onCurating.org

A conversation:

between Seth Siegelaub and Hans Ulrich Obrist

HANS ULRICH OBRIST:

My first question concerns your most recent activity. Could you tell me about this special issue of Art Press called the “The Context of Art/The Art of Context” published in October 1996?

SETH SIEGELAUB:

For a number of years now, there’s been a certain amount of interest in the art made during the late 1960s – perhaps for reasons of nostalgia or a return to the “good old days”, who knows? – and as part of this interest, over the few years I have been approached by a number of people to do an exhibition of “concept art” and I have always refused, as I try to avoid repeating myself. But in 1990, when I was approached by Marion and Roswitha Fricke, who have a gallery and bookshop in Dusseldorf with the same request, I suggested doing a project which would try to deal with how and why people are looking at this period, and thus, ask some questions about how art history in general is made. To do this, I thought the most interesting thing to do would be to ask the artists themselves who were active during the late 1960s and have lived through the past last twenty-five years, to give their thoughts and opinions about the art world; how (or if) it had changed, how their life had changed, etc. The Frickes were interested in the project, and together we began to organize it.

We began by asking artists to send us a written reply to our questions, but as not many of them had the time or interest to do this, we only had a few replies at first. Then, we began to contact the artists more actively, and Marion and Roswitha Fricke began to do taped interviews with those who didn’t reply in writing, and these written replies along with the transcripts of the taped inter-views, a total of about 70 replies, are what has been published in Art Press.

To select the artists, I picked five exhibitions which were held in 1969 – perhaps an arbitrary or personal selection, which finally is maybe not all that arbitrary – and all the artists who were in those five exhibitions were asked to reply; that is, all the artists who are still alive, about 110. What I like about the project is that we didn’t just go after the artists who have been successful, we were also – maybe even, especially – interested in the people who had not been successful, who were left by the wayside for one rea-son or another, or changed profession, etc. Thus, in this respect the replies are a more representative reflection of the period arid the peopie who lived it, than if we only asked the famous artists to give their opinion, which is what is normally done; the way art his-tory is traditionally written, i.e. through the eyes of those who have been most successful. Although I must say the replies were very uneven in the level of their reflection, ideas or critical spirit, etc. – which had nothing whatsoever to do with who was success-ful or not – and the project just became a wide range of answers running from the highly intelligent to the somewhat less intelligent.

HUO: You also said it’s about how the art world changed. Maybe this is linked to what we discussed earlier, you suggested that at that time, art was not necessarily work made for a general public, but more like a gang of friends.

SS: It was a much more limited framework, in any case, a much smaller group of people; even just in terms of numbers, even before one speaks in terms of money or power or anything like that. The artist – I could say most other people in the art world too – had an entirely different relationship with the world around them, which seems to me to be very different from what I see happening today; that’s all. So I wanted to know how – or if – the artists felt this change. Very few of them seemed to notice these differences, if I understand the replies correctly. It seems like the same old thing to many of them. Perhaps much of their formative ideas are still rooted in the 1960s? In any case, it is all there in their words.

To be continued….

Center for Curatorial Studies and Hessel Museum of Art, Bard College (CCS Bard)

Ann Goldstein Receives 2012 CCS Bard Audrey Irmas Award for Curatorial Excellence

Ann Goldstein, Director of the Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam

To Receive 2012 Audrey Irmas Award for Curatorial Excellence from The Center for Curatorial Studies at Bard College

First Year Award Given With New Audrey Irmas Prize of 25,000 USD

Award Presented at Gala Celebration on April 4, 2012 at Capitale in New York City

METROPOLIS M

Curating as institutional critique?

Symposium Kunsthalle Fridericianum

Kassel, Kunsthalle Fridericianum 26/03/10 – 27/03/10

What are the possibilities, opportunities as well as the limitations of current critical curating? On the 26th and 27th of March the symposium ‘Institution as Medium’ subtitled ‘Curating as institutional critique?’ took place at the Documenta Hallen in Kassel, discussing the current state of institutional critique.

Throughout two days the intention was to discuss the possibilities and opportunities as well as the obstacles and impossibilities of critical curating within the exhibition format, art institutions and exhibition paradigms. In the outline of the symposium the organisers (among others Dorothee Richter and Fridericianum director Rein Wolfs) define critical curating as overcoming entrenched structures and reinventing the institution, museum, exhibition hall and art society. They talk about developing socio-politically relevant exhibition formats or challenging cultural-historical facts and myths, as well as politicizing the narration of ‘shown’ content concerning gender issues, migration, economy. However throughout the presentations this proposition was predominantly anchored on the question whether such a meta-level approach is at all possible.

Friday

On Friday morning Oliver Marchart (Professor at the University of Luzern) discussed the politics of ‘biennialisation’ and voiced his reservations towards Documenta 12, curated by Roger M. Buergel and Ruth Noack. He substantiated his general point that large-scale exhibitions such as Documenta are hegemony machines, by pointing out that subjects and subject-positions are only the effects of hegemonic discursive formations. He argued that Documenta 12 had depoliticized whatever political art it showed by taking an aestheticising approach to art and that it had marginalized theoretical contextualization by outsourcing the reflection. This raises the question whether an aesthetical approach can at all have a political impact and in the context of this symposium whether a political approach necessarily generates criticality?

Maria Lind (Director, Curatorial Studies, Bard College, NY) briefly situated the historical context of Institutional Critique. She identified it as a fundamental subject in 16th century institutions where it was a vehicle to communicate the wish to govern ‘otherwise’. This historical trace makes us wonder if the recent discussion on the binary inside – outside position from which one operates in order to be critical is at all relevant. According to her, institutional critique is going through four or even five phases. Exemplified by the practice of artists such as Carey Young, Lind characterises this fourth phase as a vague critique on the whole apparatus of the art-system from an inside position. The fifth phase then draws on the position taken by ‘institution builders’ often referring to the ‘educational turn’ where cultural producers set up their own institutions such as Anton Vidokle and e-flux. To conclude her talk Maria Lind shared her opinion on the overstated believe in the role of an individual exhibition and states that the joint venture between institutional critique and curatorial practice is volatile.

The following, slightly more pragmatic talks were interspersed with the occasional artist’s performance or screening. Artist San Keller staged a lengthy public discussion with Rein Wolfs on Keller’s upcoming exhibition, concerned with the responsibility of the artist and the curator, and as such in a literal manner institutional critique was performed and incorporated.

Saturday

The second day of the symposium started with a controversial talk by Helmut Draxler (author of Curating Fatigue) ‘Ecstasy in Mediation’. It related the exploding cultures of mediation (biennials, symposia, publications) to the shift of institutions from executing a given canon to an open and flexible approach, allowing and even welcoming inside and outside critique. These institutions therefore find themselves in a state of permanent reform that is of course nothing new, though it makes you wonder what it is that constitutes this ‘institution’ today. Draxler states that in parallel the independent curator, reputed to build and maintain a more immediate, personal relation to the artist, is incorporated and we can talk about a general institution of curating. He disagrees with Beaudrillard that only mediation is left, but rather considers mediation as a productive format able to show the immediate, the unmediated. Mediation, for him, is in constant need to signify something and as such it always refers to the unmediated. The type of mediation he argues for is the ecstatic one in the tradition of Eisenstein’s over-involved actor. Ecstacy he considers not only to be an expressionist attitude but as a political intention. Is it a confirmative strategy and a useful tool to expand cultures of mediation, and a way not to distinguish the critical from the aesthetic?

Giavanni Carmine (Director Kunsthalle Sankt Gallen) and Hassan Khan (artist, based in Cairo) finally asked what good could come from a politically untainted position, so free from all power struggles. And I wonder whether this critical position has become the ethical guideline. If so for Hassan the ‘dirt’ is most interesting, certainly more than the abstract and pure. He continued by describing two types of curators he likes to work with; The ‘über-professional’ distant curator on one side, and the personally engaged, the one that immerses himself, on the other. In the first case it is clear why you are in the relationship and the second one is often messy but overly involved so in both cases what is at stake is valued.

After this stimulating and energetic discussion, the symposium returned to presentations that pragmatically reproduced examples avoiding provocative thoughts or constructive claims. However the two days enabled the professional audience to gain a comprehensive overview on the current state of institutional critique in its many forms and opened the discussion on its role and outcomes. Perhaps an elaboration on the current political and socio – economical situation would have been interesting, to understand why a certain strategy or practice is or isn’t effective. I’m thinking of possible alignment as we know them in some historical moments when theory, practice and politics find the right balance to shake and alter a situation. Referring back to Maria Lind’s comment in the overstatement in the believe in the effect of one exhibition – what would happen if we actively addressed programming as a curatorial strategy rather then the individual exhibition.

Application Deadline: February 15, 2012

Organized from April 22–29, 2012, the Curatorial Intensive will employ Instituto Inhotim as a case study to explore how curatorial practices negotiate issues of commissioning and adaptation of site-specific works; interpretation and recreation of lost and unrealized projects; and concepts of the expanded museum and exhibition, such as curating through collection building; the spatial expansion of the institution; and new forms of outreach and audience development.

The 7-day program will focus on case studies with artists who have produced works at Inhotim, as well as public panel discussions and closed-door seminars relating to context-specificity. Faculty includesKate Fowle (Director, ICI); James Lingwood (Co-Director, Artangel), Rodrigo Moura (Curator, Inhotim); independent curators Victoria Noorthoorn and Adriano Pedrosa, Allan Schwartzman(Chief Curator, Inhotim), and Jochen Volz (Artistic Director, Inhotim).

The Curatorial Intensive at Inhotim is organized in affiliation with a post-graduate seminar at the Federal University of Minas Gerais.

Application Guidelines: 10–14 applicants working internationally will be selected to participate in the Curatorial Intensive. Individuals must apply with a description of a curatorial project that he or she would like to develop through the program, a resume, a description of a recent exhibition that has made an impact on the applicant, and a cover letter. Applicants must demonstrate at least five years of curatorial experience for consideration into the program.

Fees and Scholarships: The program fee is 2,000 USD. Participants are responsible for covering travel and accommodation expenses. Scholarship packages, awarded based on merit, will subsidize or eliminate the program fees and travel expenses of several participants.

For more information and to request application materials, visit ICI’s website or contact Chelsea Haines at chelsea@curatorsintl.org or 1-212-254-8200 x126.

About the Curatorial Intensive

The Curatorial Intensive is ICI’s short-term training program that offers curators the chance to develop curatorial ideas and make connections to professionals in the field. The program takes place twice annually in New York, and in other locations in conjunction with institutional partners worldwide.

The Curatorial Intensive is made possible, in part, by grants from Affirmation Arts, the Dedalus Foundation, the Helena Rubinstein Foundation, the Horace W. Goldsmith Foundation, the Milton and Sally Avery Arts Foundation, and the Robert Sterling Clark Foundation; and by generous contributions from Toby Devan Lewis, James Cohan, and the supporters of ICI’s Access Fund.

About Independent Curators International

Independent Curators International (ICI) connects emerging and established curators, artists, and institutions to forge international networks and generate new forms of collaboration through the production of exhibitions, events, publications, and curatorial training. Headquartered in New York, the organization provides public access to the people and practices that are key to current developments in curating and exhibition-making around the world, inspiring fresh ways of seeing and contextualizing contemporary art. Since it was established in 1975, ICI has worked with over 1,000 curators and 3,700 artists from 47 countries worldwide.

About Instituto Inhotim

Instituto Inhotim is a unique site, located in the city of Brumadinho, in the state of Minas Gerais in Brazil. Inhotim offers a broad ensemble of art works, displayed outdoors as well as in both temporary and permanent galleries, all located inside a Botanical Garden of extraordinary beauty. Decreed a Civil Society Organization of Public Interest, Inhotim offers, in addition to these areas of artistic and cultural enjoyment, environmental research work, educational actions and an important program of social inclusion and citizenship for the local population. The art collection comprises over 500 works by artists of national and international renown, such as Adriana Varejão, Helio Oiticica, Cildo Meireles, Chris Burden, Matthew Barney, Doug Aitken, and Janet Cardiff, among others.

STRUCTURES IN COLLABORATION INSTITUTIONAL NETWORKING AND INDIVIDUAL STRAT-EGIES UNCOVERED

By Valentine Meyer, Anastasia Papakonstantinou, Silvia Simoncelli, Anca Sinpalean

Collaboration is a principal issue in the artistic world as a number of books, symposia, and exhibitions devoted to this topic in recent years well demonstrate. It has a variety of meanings, since the production process in the art system is very complex and comprises a lot of different phases. From the artist’s studio to the museum wall, from the curator’s idea to the public sphere, collaboration in the process of the making of an exhibition can assume very different forms and include a number of different actors.

It was especially around 1990 that a new wave of interest in collaboration arose, as it was perceived as an alternative to the predominant focus on the individual and a way to question the concepts of production, authorship and audience, a ‘Zeitgeist‘ that the theory of relational aesthetics expressed so well. Increasingly, collaboration between artists, between artists and curators, between institutions, have become more complex and difficult to describe. In approaching this topic, it is therefore necessary to try to understand “how these heterogeneous collaborations are structured and motivated. […] Concepts like collaboration, cooperation, collective action, relationality, interaction and participation are used and often confused, although each of them has its own specific connotations.

FRAC Nord-Pas de Calais / H+F Curatorial Grant

H+F Curatorial Grant 2012

FRAC Nord-Pas de Calais

Han Nefkens (H+F Collection) and Hilde Teerlinck (Director of the FRAC Nord-Pas de Calais) will select the new candidate. The selected person will become part of the FRAC’s team as an assistant curator, coordinating local, national and international exhibition-projects. The grantee selected for the period of 12 months will also be responsible for the coordination of ArtAids projects wich focus on creating awareness about HIV/Aids and tackling the stigma connected with it. See www.artaids.com

She / he will receive in exchange a grant for 12 months (2012) that will help finance her/his living and travel expenses. An excellent knowledge of English is desired, knowledge of French and Dutch would be helpful. The candidate will have to install her/himself in Dunkirk for the mentioned period.

This project has been made possible thanks to the generous support of Han Nefkens (journalist, writer and art collector), which enables the FRAC Nord-Pas de Calais to reinforce the development of a strong and active policy of patronage around its activity.

Please send your application containing a recent CV (including a photograph), a exhibition project based on the collection of the FRAC Nord-Pas de Calais (max 1 A4) and an motivation letter before December 15th, 2011 to:

FRAC Nord-Pas de Calais:

Hilde Teerlinck

930 avenue de Rosendaël

59240 Dunkerque, France

Tel. 03 28 65 84 20

www.fracnpdc.fr

project@fracnpdc.fr

TO SHOW OR NOT TO SHOW

|

|

| Frontispiece to Ole Worm’s Museum Wormianum, 1655 |

|

Jens Hoffmann e Maria Lind intrecciano una vivace discussione su due diverse visioni della curatela. L’una che intende esplorare il formato della mostra in tutte le sue vie, fino a quelle meno battute; l’altra che ha una concezione “espansa”, la cui finalità principale è quella di far sì che l’arte divenga pubblica. Il problema resta quello della qualità che nell’attuale parossismo produttivo sembra essere messa a serio rischio.

Continua….http://www.moussemagazine.it/articolo.mm?id=759

A PLEA FOR EXHIBITIONS

Robert Gober, Untitled (Shoe), 1990

From “Dead! Dead! Dead!”, Ydessa Hendeles Art Foundation, Toronto, 1997. Courtesy: Ydessa Hendeles Art Foundation, Toronto. Photo: Robert Keziere.

È arrivata l’ora di sbarazzarci di categorie espositive obsolete e poco stimolanti – la mostra monografica, la retrospettiva di metà carriera, la collettiva. Negli ultimi quattro decenni, la diversificazione delle pratiche artistiche ha suggerito ai curatori un approccio nuovo alla loro attività. Il concetto di organizzazione di mostra tradizionale è stato superato a favore di un florilegio di “eventi”, conferenze, performance, film… Un crescente numero di curatori, da Catherine David a Okwui Enwezor, da Hans Ulrich Obrist a Ute Meta Bauer, a Matthew Higgs, ha introdotto modelli alternativi orientati tanto al dibattito quanto al confronto con altri campi del sapere, tanto al coinvolgimento politico quanto a modalità radicali d’esposizione. Jens Hoffmann ci offre uno spaccato di quest’entusiasmante mutazione.

continua…http://www.moussemagazine.it/articolo.mm?id=569

UNIVERSO SZEEMANN

Nel corso del convegno dedicato al grande curatore svizzero, si è parlato di come il modello curatoriale Szeemann abbia influito sull’odierno significato di curatela

Il 14 e 15 Novembre l’auditorium della fondazione Querini Stampalia a Venezia ha ospitato il convegno ‘Harald Szeemann in context’ organizzato dall’Istituto Svizzero di Roma. L’evento, nato da un progetto di Stefano Chiodi, Salvatore Lacagnina e Henri de Riedmatten, é coinciso con il decimo anniversario della Biennale curata da Szeemann e si è proposto di analizzare criticamente sul piano professionale e personale l’ormai mitica figura del curatore svizzero.

Attraverso l’intervento di dieci relatori internazionali, critici, curatori e ricercatori, che si sono susseguiti nelle due giornate di convegno, è stato tracciato con successo il profilo di Szeemann, l’originale percorso professionale caratterizzato dalla duplice natura di curatore indipendente e al contempo attivo in ambito istituzionale e la sua eredità. L’intento di storicizzare e interrogarsi sull’influenza del modello curatoriale Szeemann ha aperto e lasciato in sospeso molteplici questioni inerenti al ruolo delle istituzioni museali contemporanee e all’odierno significato di curatela.

Il primo giorno di convegno è stato particolarmente significativo per circoscrivere e contestualizzare la figura del curatore svizzero, partendo dal suo operato per poi trasportare le riflessioni sul piano pratico e contemporaneo al fine di comprendere come Szeemann abbia influenzato le generazioni di curatori seguenti.

Il compito di aprire le due giornate di confronto è stato affidato a Tobia Bezzola, curatore della Kunsthaus Zürich e di Harald Szeemann – with by through because towards despite – Catalogue of all exhibitions 1957–2005, la più importante pubblicazione retrospettiva che presenta il lavoro di Szeemann nella sua totalità. L’intervento di Bezzola è stato rilevante per approfondire le modalità di coesistenza tra i progetti indipendenti e il singolare ruolo di “permanenter freier Mitarbeiter” che Szeemann ha ricoperto dal 1981 all’interno della Kunsthaus Zürich. Le problematiche più significative sollevate nella prima mattinata hanno spaziato dalla caratteristica mise en scène delle mostre, che ha raggiunto il suo picco inWhen attitude become form (Kunsthalle Bern, 1969), alla definizione di fallimento rispetto alla mostra Happening and Fluxus (Kölnischer Kunstverein, 1970), nella quale Szeemann considerava di aver dato troppa libertà agli artisti. Inoltre è emerso il costante rapporto che il curatore svizzero aveva con i concetti di anarchia e utopia che hanno profondamente influenzato la sua pratica (un esempio importante è la serie di mostre iniziate nel 1978 a Monte Verità) e i termini in cui egli si autodefiniva anarchico.

Gli interventi che hanno seguito, rispettivamente di Philip Ursprung, professore di storia dell’arte e architettura alla Eidgenössische Technische Hochschule di Zurigo, Beat Wyss della Staatliche Hochschule für Gestaltung di Karlsruhe e a concludere, Bice Curiger curatrice dell’attuale Biennale arte, si sono concentrati sull’eredità lasciata da Szeemann. La caratteristica non linearità storica delle mostre ideate dal curatore svizzero (“it was about space” dice Ursprung) e la propensione verso un’ideale opera d’arte totale: “needless to say a Gesamtkunstwerk can only exist in the imagination” (da Hans-Ulrich Obrist, Mind over matter – interview with Harald Szeemann, Art Forum International 11/1/1996) hanno contribuito alla trasformazione del dispositivo mostra, alla riconsiderazione dell’autorialità del curatore, allo stravolgimento degli equilibri tra artista e curatore e alla ricollocazione del ruolo dell’istituzione museale.

Il secondo giorno di convegno si è aperto con le relazioni di tre giovani ricercatori: Mariana Roquette Teixeira, Pietro Rigolo e Lara Conte. Il prezioso lavoro di analisi che hanno svolto negli archivi Szeemann ha riportato alla luce alcuni casi studio significativi per comprendere il ricco apparato documentale che corredava le mostre e per approfondire le modalità operative progettuali del curatore svizzero. Mariana Roquette Teixeira dell’Universidade Nova de Lisboa si è occupata di analizzare la mostra Großvater: Ein Pionier wie Wir (1974), mentre Pietro Rigolo dell’università IUAV di Venezia ha incentrato il proprio intervento sul ritrovamento di una serie di documenti relativi ad una mostra mai realizzata: La Mamma. La mostra doveva idealmente concludere una trilogia iniziata con Le macchine celibi (1975-77) toccando tematiche come la storia delle religioni e del femminismo, il pensiero teosofico, la letteratura, la psicanalisi, l’antropologia e la storia dell’architettura percorrendo “la storia delle donne dalla più grassa e vecchia alla più magra”. La relazione di Lara Conte, invece, ha delineato i rapporti tra Szeemann e l’Italia, considerando i contatti con gli artisti italiani del tempo e l’incontro con Germano Celant.

“La caratteristica non linearità storica delle mostre ideate dal curatore svizzero e la propensione verso un’ideale opera d’arte totale hanno contribuito alla trasformazione del dispositivo mostra, alla riconsiderazione dell’autorialità del curatore, allo stravolgimento degli equilibri tra artista e curatore e alla ricollocazione del ruolo dell’istituzione museale.”

Al termine del secondo giorno gli interventi di Glenn Philips che ha definito l’importanza dell’archivio Szeemann acquisito dal Getty Research Institute di Los Angeles e Michele Dantini che ha dedicato la propria trattazione alla figura di Germano Celant, al fine di ricomporre e riconsiderare il processo di appropriazione del modello curatoriale Szeemann in ambito italiano. A Mary Anne Staniszewski, autrice di The Power of Display: A History of Exhibition Installations at the Museum of Modern Art, è stato affidato il compito di concludere queste due giornate di convegno, illustrando la trasformazione del concetto di curatela attraverso una visione panoramica del contesto politico contemporaneo e delle sue trasformazioni in ambito artistico istituzionale. L’intervento della Staniszewski si è ricongiunto alle riflessioni politiche emerse il primo giorno, regalando al pubblico una serie di domande aperte:

la mostra è ancora un dispositivo attuale? Che importanza ha nello scenario politico contemporaneo il concetto di anarchia? Come si configura ad oggi il rapporto tra artisti, curatori e istituzioni museali?

Francesca Colussi

http://www.domusweb.it/it/art/universo-szeemann/

THIRTY ONE POSITIONS ON CURATING

Tadej Pogacar

All curatorial practices should discuss / question their position within the actual art system. They should not hide their ideological backgrounds, but openly analyse them. Specific relations between the artist, curator, public and institution are a very important and sensitive topic – especially power relations, that usually stay hidden.

Jesús Fuenmayor

Curating is a specialism (still not even a discipline outside the centres, where it mostly takes place) with very uneven developments. Thus, that which seems an urgent necessity in some places, like the need for creating academic spaces for its development (which is the case for Venezuela and the rest of Latin America), in other places seems excess to requirement. As I exercise my curatorial practice from the margins, the future development of curating as a discipline is a crucial subject for me. In my country, as in almost all of Latin America, we face the total absence of an academic scope that offers the possibility of education in this area above fourth grade, not to talk about professional training. Such an education, ideally oriented to stimulate investigation on a theoretical level or at the very least specialized studies (logistic, tactical and technical), is needed to create the minimum of consensus on the existence of curating as a practice. Why is it that in Latin America the only existing consensus curating is the one that precedes it, from its validation in the centres? Yes, as García Canclini says, in the evolution of the protagonist subjects of the museums (understood is the museum as the cornerstone of the spreading of art), the last link is the curator. So, if the curators presence is so determining, from where comes the resistance to think of it as a field or discipline? Consequently, it would be necessary to ask ourselves: Is this a productive resistance?

Verena Kuni

If the accent here is on “openly” and “discussed”, one might automatically think of certain restraints like the politics of economy (including the so called attention economy) and the whole question of marketing (not only the so called “art market”). We see a lot of really boring, conventional shows and whole exhibition programs that are marketed as if they were pure innovation and inspiration – not only by the institutions and their curators, but also by the press. This fact as such is not really a problem, even if you think about all the money and energy that went in these projects and not into others: First of all, there are obviously enough people (including the sponsors as well as a public) who obviously want to see exactly these kind of shows – and I’d even concede that many of these are in their own way well done. And then there are always enough really fascinating and inspiring projects in case you are really looking for them. But as a matter of fact this situation is not usually discussed at all, at least not “openly”. Perhaps one main reason for this is that everybody knows the underlying structures all too well. And of course even the best curatorial study programs won’t help us to get rid of them. Personally (and closely related to my own practice) I am far more interested in questions like these: How to make invisible/non-material “things” visible without forcing them into mere representation? How to deal with heterogeneous formats of ideas within one bigger framework, in order to create some kind of communication or at least some productive tension between them? How to create interfaces for people that invite them to actively relate to something – perhaps a set of ideas – offered to them?Thus, I would love to see questions like these discussed more intensely. Yet I might like to add: In the end, when it comes to curating I consider far more important what is done than what is discussed.

Adrian Notz

I don’t want to see any topics on curating more openly discussed. I don’t see the point in talking about curating as curating. Because curating should be discussing art not itself, curating. Not curating curating.

Simon Lamunière

Architecture

Iben Bentzen

I have four topics I would like to see more openly discussed: 1. Creative curating: what happens when the curator is a collaborative partner in the creative process of creating and defining the works? In which ways can the contemporary curator be viewed as a coach? 2. Creating web exhibitions: if more and more virtual and digital exhibtion spaces emerge in the future, what does that demand from the curator? From the artists? From the viewers?3. The artist is the curator is the artist: many curators today are artists and vice versa. It gives an insight into both roles and this knowledge is important to understanding the different steps of building up an exhibition or creating an art piece. When and how can the myth of that these two roles needs to be separated be killed? 4. Why are there so few educations focusing on curating?

Continue on Oncurating.org

ART AS CURATING ≠ CURATING AS ART

Jens Hoffmann & Julieta Aranda

Jens Hoffmann: I am entering this conversation from the position of the curator—a curator who has often been accused of taking a very authorial and creative position in the creation of exhibitions. I am emphasizing words like “author” and “creation” on purpose to express my place in this conversation, and my overall standpoint in the realization of exhibitions. I am not an art historian—the traditional background of a curator—nor did I study curating. Rather, I consider myself an exhibition-maker in the tradition of Harald Szeemann and Hans Ulrich Obrist, both of whom have had to deal with similar critiques in regard to their creative approaches when organizing exhibitions. The group show is our medium, but none of us has ever done anything to a work of art that was not appropriate or forced artists into a context they did not want to participate in. Criticism usually comes from the outside—never from the artists we collaborate with—and skepticism is particularly strong in the United States. I recently had a conversation with a young writer and curator who said he did not want to be progressive in his work as a curator but focus his energy on curating large-scale monographic shows of established artists. I thought that was very telling about the role of the curator in an institutional setting. I see my own trajectory, which grows out of Szeemann’s practice, as forming temporary alliances with artists to produce grand narratives that are bigger than the sum of their parts: exhibitions with an epic dimension, if you will, which reconnect to my formative years as a theater director. My points of reference are Erwin Piscator and Bertolt Brecht and filmmakers of postwar France and Italy. Jean-Pierre Melville and Michelangelo Antonioni are especially important influences in their authorial approach to filmmaking. In the field of contemporary curating, I think that Okwui Enwezor is the most gifted, but I am also a big fan of the curatorial work of Ydessa Hendeles. She has been a big influence on me, perhaps more so than any of the other people mentioned here. Her way of making exhibitions is certainly on the border of artmaking. What I like about her is that she brings very personal elements to her exhibitions—emotional, almost romantic—and she is very interested in the staging of her shows. She is the best installer of exhibitions that I know. Her shows are more than perfect, if you ask me.

Julieta Aranda: Since you entered this conversation as a curator, I should state my position too and say that I am entering it as an artist. Yet, I am an artist that has often been mistaken for a curator, since I frequently create participatory projects. In the beginning, it was quite frustrating to constantly encounter skepticism for my work, but over time I came to realize that there is a place in which the lines between what constitutes artistic practice and what constitutes curatorial practice can be blurred. I would like to use this conversation to try to define this blurred space—this intersection—and how it can be productive on both sides of the blur. I am very curious as to how you understand the relationship between artist/curator—the important differences and the place in which these roles are perhaps even complementary.

J Hoffmann: What you say is interesting, as there is a history of what you describe as a “blurred space” of intersection. Just think about people like Seth Siegelaub, for example, or more recently Matthew Higgs—an artist as much as a curator. Then there are artists who curated exhibitions, at times even run art spaces. This “blurred space” has a long history. I have learned a lot from watching artists curate. Most recently, I invited Paul McCarthy to curate a show at the Wattis Institute in San Francisco, where I am now the director. It was a terrific experience: seeing him select the pieces, seeing him install work in very different ways as compared to a curator. Artists have a different approach to curating—one that is less conformist and often more creative and unpredictable. There have been fantastic shows curated by artists that I always mention as some of my favorite exhibitions: The Play of the Unmentionable (curated by Joseph Kosuth), Americana (Group Material), Mining the Museum (Fred Wilson) or before that, in the late 1950s, This is Tomorrow (Independent Group) and many more. All of them influenced me enormously, probably more than exhibitions curated by what we would call “proper” curators. I have always considered myself a proper curator, though even that has been disputed at times. People have said I am so creative that my work really borders on artmaking, but these kinds of comments miss the point as they overlook what my work actually says about curatorial practice. Someone who is important for me here is Liam Gillick, with whom I’ve had fantastic discussions about exhibition-making and the roles of artists and curators. I remember him saying once that he thought that it was curators who changed art in the 1990s, not so much artists. I am not sure if that is right—he probably went a bit too far—but it was an interesting point to consider and speaks to the importance of curators in the field of art today.

J Aranda: Sometimes I wonder if there is really a need to keep roles so strictly separated or if curating is an entrenched practice merely because of tradition. I would be very curious to know what you consider to be the difference between artist-curated shows and curator-curated shows. In my case, I think more and more about the possibility of an extremely flexible approach in which it would be possible to articulate polysemic positions that can be either artworks or exhibitions. Somehow the idea of exploring the intersecting space between both practices seems more interesting to me than it is to delineate the boundaries of each. A good example is Obrist’s DO IT exhibitions, which I find incredibly successful as artworks.

J Hoffmann: I think you have a point there in regard to the separation of curating and artmaking. It has a lot to do with tradition, habit and the historical development of art and museums. Do not forget that until recently, curators were mostly art historians. The majority of curators today still are art historians, but you also have a new kind of curator that follows the model of someone like Szeemann, for example, and works very closely with artists. I think Obrist played a big role in this development as well, and you already mentioned DO IT, one of the most interesting shows in recent history in terms of its innovative qualities. I am not sure, however, if it would be innovative with regard to the history of art. That is why I would always vote for a separation of these practices—artmaking and curating. Curating is not really an artistic practice. At best, it can be called a creative practice. Also, most of the time, the boundaries between these practices are being crossed more by artists than curators. I have not found one curator yet that considers her or himself an artist. If they do, they cease to be curators. Perhaps all of this will not matter much in the future, but one needs a different set of skills to make shows than to make art. Artists I’ve worked with are always surprised about the amount of work they have to do as a curator, apart from the selection of artworks. All the administrational elements are really shocking to them!

J Aranda: Something that is odd to me is to see how the crossing of boundaries changes modes of working for both artists and curators. Of course, there is a long tradition of curators coming from art history, and the same long tradition of rational, well-thought-out survey exhibitions to illustrate art-historical topics. It is very good to see that linear mode interrupted by a more intuitive approach to curatorial practice, which complicates the relationships between works or that articulates a point altogether different from what could be said by historical analysis. However, I also notice that there have been more and more artists that are making use of investigative methodologies common to an art historical approach. This can be interesting ground for productive confusion, and thus it makes me wonder why you think that the moment a curator might consider him/herself as an artist, they would not be a curator.

J Hoffmann: Of course artists have heavily influenced curators, not only through the work that they make when they curate but, more often, simply through their own artwork. Look at how much influence the practice of institutional critique and conceptual art have had on curators over the last forty years. It is interesting that you would call new ideas in the field of curating more “intuitive.” I disagree with that, but I think what you mean is that they can be, perhaps, more personal. It is difficult to generalize. People still tend to look at new forms of exhibition-making as one movement—as one overall idea—even though the efforts of most curators that fall into this category can be quite different in their methodology and, in many cases, do not even relate to one another. But to answer your question, if a curator considers his or her work to be art, then he or she is not a curator anymore simply because exhibition-making, as I understand it, is not an artistic practice. It is still about some form of scholarship, even if it is very creative and personalized. But you are right in that it is becoming harder and harder to define.

J Aranda: I think I should clarify. When I say “intuitive,” I don’t mean misinformed, but I also don’t mean strictly personal. What I find fascinating about the curatorial approach that we are discussing is that it is not following the logic of art history as we know it but is also not using work to serve a personal logic. In some way, it seems to be structured around relations of complicity, where all the parts involved remain active as the statement is articulated. That doesn’t talk to me only about exhibition-making but also about artmaking and about how these two things are becoming inextricably tied at a certain level.

J Hoffmann: Yes, I understood that you did not mean “misinformed,” but I would be careful with the use of the word “intuitive” in the context of curating. I think what you mean is nonacademic—idea-based. Looking at my own work, I think I am intuitive to some degree but perhaps less when it comes to making an exhibition and more when it comes to an initial response to artworks that I analyze intellectually. I understand your ideas of the blurring of these boundaries, and they make a lot of sense; it is just a very particular discourse that I am personally not so fond of. In some funny way, I sometimes think I am a conservative curator: I like objects, I like to work in gallery spaces, I like all the details associated with exhibitions. The things I fundamentally reject are common forms of exhibitions and the categorization of exhibition genres, and that alone calls everything into question.

J Aranda: The way in which you describe your relationship to curating is often with regard to the group-show format. I am curious as to how you see the one-to-one relationship between a curator and an artist. For example, I know that you often work with Tino Sehgal. How does your process change in such a case, if at all?

J Hoffmann: I think that the group show is the exhibition format in which curators can be the most creative. Here she or he can bring in their vision in regard to artists, artworks, themes, etc., and tie all the elements together following one larger concept. I have looked extensively at this particular exhibition format and worked—especially in earlier exhibitions—on conceptualizing the process of making an exhibition. Today, my exhibitions continue to contain a self-reflexive element, but that is only one of many concerns. I am much more interested in the idea of staging exhibitions as an overall creative and artistic environment that the audience can immerse themselves in on a number of levels. When a curator is working with an artist on a solo exhibition, the one-to-one relationship is always different and entirely dependent upon who one works with. But usually, when working on a solo show—and I have to say that all the ones I have done are not survey exhibitions but project-based solo exhibitions—I try to look very carefully at the artist’s work and then try to find a format for the exhibition that is based on a particular element of the artist’s practice. It is a long process, and it is one of the most interesting things for me: the challenge of how to find the most adequate form of exhibition for a particular type of work. Artmaking has changed so radically over the last century; yet, we still use display strategies—exhibition formats that have been with us even longer. I am trying to challenge this by looking at the artwork, by talking to the artist, in order to find the best possible format for a solo presentation. But now we are talking too much about exhibition-making from the curator’s point of view. Tell me more about your thoughts in this respect. How do you start thinking about curating an exhibition, for example? How is that related to your work as an artist? Are there very strong connections, or is it more of a fluid form of exchange between the two?

J Aranda: I understand your affinity for the group show. The format is interesting to me as an artist because it allows one to see how work functions in a certain context. Why I ask about your role when working one-on-one with an artist is because I used to think about curators in the classical, art-historical sense—as the keepers of the record—those in charge of making sense of the world around them, much like the function of one in charge of continuity in filmmaking. However, when I think about what I call “intuitive” curators, things shift. When I mentioned before relations of complicity, it is because I have come to realize that this becomes a very strong and important component of the working process—at least in my case—much more so than the directives and guidelines of art history.

As to your questions, I don’t think I have ever curated an exhibition. What happens is that some of the projects that I have worked on with Anton Vidokle tend to be confused with curated exhibitions. I believe this is because we were using a participatory model so that the content would come from people that were complicit with a certain idea, while we could focus on the structure. These projects are completely related to our preoccupation with the notion of circulation and its aesthetic potential. In the case of our video rental store, this became the idea of making a structure that would complicate the terms of access and display of film and video work, while trying to lay the groundwork for the creation of an open archive. And in the case of Pawnshop, we tried to focus on the moment in which value is generated within the processes of exchange and circulation of artwork. Obviously, we were relying greatly on the participation of all the people that have taken part in these projects, but I really don’t consider this approach curatorial, nor do I consider these projects to be curated exhibitions. I would be open to say that they sit in a gray zone of confusion where disciplines intersect, and maybe this is why I am interested in talking to you about this in detail.

J Hoffmann: I would not consider the video rental project or Pawnshop an exhibition or an artwork. The first was a platform for the dissemination of works by other artists for which you invited many curators to select videos; the second was a structure that would offer artists an opportunity to expose and circulate their work within the particular circumstances of a pawnshop, where pieces were reduced to their commodity value. You do not ever say that these were artworks or exhibitions. You always refer to them as projects.

J Aranda: In the case of the video rental project, the work does function as a platform. To me this doesn’t take anything away from the understanding of it as an artwork, as I believe that the status of what is and what is not an artwork is not related to formal qualities. As you know, there are many other artists that are working with archival models and exploring the restructuring of certain situations by way of other works. I think that at this point, we can say that an artwork can take the form of a structure, especially in the case of this work, which was chiefly concerned with the aesthetic potential of circulation more than with its own content. With Pawnshop, again the idea was not to offer visibility to other artists but to explore the structure within which value is constructed, which needed the participation of others in order to function. I think that it is possible to make work that contains work by other artists but is independent in meaning from the work that comprises it. I understand that it can be tricky to analyze such projects, but I also think that this model of production makes things interesting. Maybe this is why I am now more interested in complicating the boundaries between disciplines—not because I am interested in becoming a curator or because I think that curators should define their role in a more or less ambiguous way—but because I think that the potential of this constantly shifting ground is turning the field that we share into something incredibly interesting, far more interesting than anything else going on right now.

J Hoffmann: I understand exactly where you are coming from, and it makes perfect sense. I am intrigued by your desire to create the new and to form alternative ideas of all of these practices. I see that what you do is a clear continuation of works that I would also connect to some artists involved with so-called relational aesthetics, but expanding the idea of outside participation and widening the idea of an exhibition as an artistic medium. It is interesting to me that I needed you to elaborate on it further in order to be able to fully understand your intentions. I am not sure if the overall idea was really apparent to everyone who followed these projects. I have also always thought of The Next Documenta Should be Curated by an Artist as an exhibition and not so much as a book, and I think that was also not clear to many people. For me, curating is always about widening the understanding and formats of exhibitions and never so much about doing the same for art. That is the artist’s job!

Tratto da: Art Lies, Issue 59

CURATORS IN THE FIELD OF CONTEMPORARY ART

Beatrice von Bismarck

Since the 1990s the profession of the curator has enjoyed a level of attention previously unknown. Beginning with the historical landmark of the figure of Harald Szeemann, a star cult developed around curators that, as a number of lectures and publications of recent years suggest, has banished artists and art critiques to a lower rank in the field. This intense engagement with the professional profile, with the tasks and demands of curatorial praxis, is thus in no small measure due to a conflict of hierarchization that has almost necessarily emerged within the field. The artist and initiator Susan Hiller opened the multiyear lecture series The Producers: Contemporary Curators in Conversation in Newcastle by asserting that the curator has replaced art critics and artists today: a statement that was subsequently taken up, discussed, and, with various results, denied by the speakers. If one examines the arguments that have been advanced in the tribunals on the status of the curator, it is striking that the embattled front by no means describes a clear line but is rather characterized by interruptions, abrupt turns, and spatializations. For while curators on one side are enthusiastically granted an extraordinary status ‘on par with the artist’, which is seen as progress in the advancement of the field, on the other side this very similarity with the artist’s role has triggered vehement criticism and hostility. The relevant perspective shifts in accent, here on the definition of the work done, there on the process of organizing a public sphere or on adapting to consumer behavior once again, can transform from praise of a prominent subject position for the curator to condemnation as presumptuous and improper. What is on trial is not just the redistribution of social privileges that would go along with a rise in the professional image of the freelance curator but also, quite fundamentally, the nature and efficiency of participation in the processes of constituting meaning.

Perhaps more than any other profession in the field of art, curatorial praxis is defined by its production of connections. The acts of collecting or assembling, ordering, presenting, and communicating, the basic tasks of the curatorial profession, relate to artifacts from a wide variety of sources, among which they then establish connections.

The possibilities for such connections are manifold and, once the objects have been removed from their original contexts, can also be constructed anew. As exhibited objects, the materials assembled are ‘in action’: that is, they obtain changing and dynamic meanings in the course of the process of being related to one another. Ideally, these connections result from formal and aesthetic features or from content, but they also relate to the corresponding cultural, political, social, and economic contexts that attach to the exhibited objects their historicity.

In 1998 Zygmunt Bauman located the curator’s position “on the front line of a big battle for meaning under the conditions of uncertainty, and the absence of a single, universally accepted authority.” To put it simply, he was hoping to find the roots of a semantic production based in processes of connection in the postmodern transformations in the field of art. Against the backdrop of such antithetical assessments of the role today, one also hears in Bauman’s formulation the two essential conflicting poles between which the current, more highly differentiated debate has evolved. On the one hand, there is the positive assessment that the figure of the curator represents the hope for finding footing again in the jungle of meanings that has resulted from the loss of clarity and binding norms.

On the other, there are reservations about giving the installation a new position of authority that lays claim to special powers to interpret the processes of connection. If we choose not to view the current ‘curator hype’ and star cult as simply a side effect of the enormous growth in exhibition activity as part of today’s event culture but also admit it has critical modes of action and effect, then the relationship between these two antithetical assessments of the phenomena becomes more significant. When trying to put curatorial practice in perspective, which is necessary if it is to have a critical potential, this relationship proves to be an essential aspect, which can for its part be made useful as an element of a critical praxis. Hence the remarks that follow will be devoted to it. They are based on the assumption that a specific variety of criticality isappropriate to curatorial practice, given its procedure of creating connections.

Art’s claim to autonomy is one of the main points of reference for the reservations raised about the role of the curator today. The art sociologist Paul Kaiser observes along these lines: “The success of curators as social figures in recent years derives from the old dilemma of art in the (post-)modern age, i.e. the need for art to assert its supposed autonomy in a market heavily regulated by economic factors.” In comparison to earlier decades, he identifies the specific nature of the present situation as the fact that the other authorities that have previously responded to art’s need for commentary “newspaper criticism, academic study, educated patronage (…)” have “largely ceased to be parallel sources of creative production (…)” in our “fun, consensus and aspirin society.” The commentaries on the figure of the curator mentioned above reflect this assessment of a crisis. Even if they disagree on what triggered the crisis, art theory, art criticism and even art itself have all been held responsible, they all share the view that the genesis of the curator position can be attributed to the inadequacies of other positions in the field of art. Kaiser’s formulation makes this judgment concrete and at the same time once again puts the curator in the service of art as ‘marketing manager’, ‘artistic intellectual’, or ‘amateur trend scout’. The basis for the discussion is a development in the field of art that began in the 1960s with the rapid growth of activity, increased differentiation within the art field, and the associated rise of new professions, including both the freelance curator and the increasingly specialized curator associated with an institution. Ever since curators have been sharing the tasks involved in communicating art with scholars in various disciplines, gallery owners, critics, and teachers. The ‘dealer-critic system’ that Cynthia White and Harrison White identified in their groundbreaking 1965 study of the development of art institutions in France in the nineteenth century as the structure of the art field in the modern era had added a whole series of new players. Enhancing the status of the freelance curator to the extent that is done in the current discourse means an essential shift and concentration of the power to constitute meaning that had previously been distributed more equally among various authorities for communicating such meaning. The trend was encouraged by the deprofessionalisation that began at the same time in the 1960s as these processes of increased differentiation in the filed and have clearly accelerated again in the 1990s, in a kind of countermovement to efforts at professionalisation institutionalized in courses and schools. In these trends, two fundamental developments of art reveal their consequences for the roles and tasks in the field of art: increasing conceptualization, on the one hand, and a focus on context, on the other. Artist’s encroachments on tasks and roles that had been assigned to other players in the field of art were closely connected to this concentration on the discourse of art. Because these other players in turn exchanged and appropriated various activities and positions among themselves, since not only artists but also critics and curators can write, create exhibitions, teach, and sell art, because aspects of both harmonization and indistinguishability emerge in these mutual transfers, it is also possible for professionals who do not explicitly think of themselves as artists to participate in the elevated social status of the ‘artist’.

The debate over power and status appears to become especially heated around the profession of the freelance curator, who is thus not tied to an institution. The basis for this is the social status associated with communicating art, which is part of the various professional disciplines in the field of art. Institutions that mediate between art and the public, be they museums and collections in private or public hands, exhibition houses, commercial galleries, magazines, publishing houses, universities, or art colleges are authorities that consecrate and legitimize. In their dependence on their objective relations and positions in the field, they participate in the process of evaluating art as art. The players active in them and for them, curators, gallery owners, critics, publishers, teachers, and theoreticians, carry out these processes. For its part, the effectiveness of these players develops in dependence on their position in the field, in their relationships of powers relative to other players and the institutions.

to be continued on

http://www.on-curating.org/documents/oncurating_issue_0911.pdf

THE PRODUCTION OF THE PUBLIC. EXPERIENCES FROM MUMBAI

Prasad Shetty & Rupali Gupte

The idea of public is central to urban planning. Most decisions in planning processes are taken in the name of the public. Public infrastructure, public spaces, public amenities, and so forth, are commonly used terms in the planners’ vocabulary. Public here is agreed as all people or everybody. There is an entirety promised in the idea of the public, which is understood to be a clear entity. As any ambiguity or complications in the idea of public would destabilize planning, conceptual discussions on this subject are taboo for the discipline. Hence there is a conceptual closure of the idea, where the public explicitly means a definite entity. The messy urban conditions of Mumbai provide a clear illustration of how opening up the idea of public would destabilize planning processes.

For instance, in the design of streets, a certain width is considered to accommodate pedestrians and vehicles. However, a street in the city of Mumbai is often used and claimed in multiple ways – by hawkers erecting their stalls, by shops extending their boundaries, by new shops opening, and so forth. Slowly, the street converts itself into a shopping place (fig. 1). Being unable to accommodate the new activities, the street becomes congested and becomes an instance of the failure of the plan. While making the plan, the planner assumes the street to be a public space (infrastructure) – to be used by all people – but only for walking and driving. The planner further assumes the public to be pedestrians and car drivers who have no claims over the road, but use it to pass through. The planner can only handle such clearly defined and closed ideas of the public (without claims) for designing the street. Any attempt at a conceptual opening-up of the idea would make the situation unmanageable for the planner. Closer material examination of how streets are worked out as public spaces would clarify the difficulties arising from handling the conceptual opening up.

ONCURATING.org ISSUE 11 - Public Issues

POLITICS OF INSTALLATION

Boris Groys

The field of art is today frequently equated with the art market, and the artwork is primarily identified as a commodity. That art functions in the context of the art market, and every work of art is a commodity, is beyond doubt; yet art is also made and exhibited for those who do not want to be art collectors, and it is in fact these people who constitute the majority of the art public. The typical exhibition visitor rarely views the work on display as a commodity. At the same time, the number of large-scale exhibitions—biennales, triennales, documentas, manifestas—is constantly growing. In spite of the vast amounts of money and energy invested in these exhibitions, they do not exist primarily for art buyers, but for the public—for an anonymous visitor who will perhaps never buy an artwork. Likewise, art fairs, while ostensibly existing to serve art buyers, are now increasingly transformed into public events, attracting a population with little interest in buying art, or without the financial ability to do so. The art system is thus on its way to becoming part of the very mass culture that it has for so long sought to observe and analyze from a distance. Art is becoming a part of mass culture, not as a source of individual works to be traded on the art market, but as an exhibition practice, combined with architecture, design, and fashion—just as it was envisaged by the pioneering minds of the avant-garde, by the artists of the Bauhaus, the Vkhutemas, and others as early as the 1920s. Thus, contemporary art can be understood primarily as an exhibition practice. This means, among other things, that it is becoming increasingly difficult today to differentiate between two main figures of the contemporary art world: the artist and the curator.

to be continued on

http://www.e-flux.com/journal/view/31

THE POLITICAL POTENTIAL OF CURATORIAL PRACTISE

Gerd Elise Mørland and

Heidi Bale Amundsen

Can curating make a change? And if so: how? As a result of the expanding market for contemporary art, the upsurge of biennials, art fairs and large group exhibitions, and the construction of numerous new museums for contemporary art during the 1990s, the role of the curator has undergone profound changes. From being a marginal character working within the confines of the museum, the curator has come to inhabit a freer and more centralized position within the artworld at large. Correspondingly, the critical focus has turned from the individual artworks to the overarching structure of the exhibition. As there has been a displacement of power from the artist and the curator, critics are now considering the exhibition an utterance in its own right. This has given the curator the means to agitate, speak and to be listened to. As a consequence, within the last few years we have seen an increasing number of curators utilizing their newfound power for political purposes, aiming to change societal structures. Certainly, political exhibitions can hardly be considered a new phenomenon. What we find new

though, is the way of expressing these political concerns. Prior to the institutionalizing of the curator’s role and the shaping of it as we see it today, the political was often expressed through the exhibitions’ content. But as the role of the curator changed, the curatorial methods

changed with it. This implicated what we consider a radically new way of working politically as a curator. While politics had normally been expressed through the exhibitions‘ content and thematic, curators could now activate art‘s political potentialthrough curatorial form and structure as well.

ONCURATING.org ISSUE 04

to be continued on

http://www.on-curating.org/documents/oncurating_issue_0410.pdf

LA FORMAZIONE CURATORIALE IN ITALIA, UNA STORIA RECENTE

Maria Garzia e Frida Carazzato

In Italia le scuole per la formazione curatoriale sono nate da poco più di un decennio, nello stesso periodo la figura del curatore è diventata oggetto di dibattito al fine di definirne la pratica. Corsi di specializzazione e corsi post-laurea promossi sia nell’ambito della didattica universitaria che da enti e fondazioni private, hanno posto l’accento su una professione relativamente recente di cui evidentemente si comincia ad avvertire il bisogno di teorizzarne la pratica. La mancanza di una definizione univoca di tale professione e dall’altro lato la molteplicità di competenze che la caratterizzano, sono alla base della questione sulla sua “formazione”. Avendo partecipato ad un programma di formazione in pratiche curatoriali all’estero (l’Ecole du Magasin di Grenoble), una situazione di per sé favorevole e stimolante per un’analisi a distanza, abbiamo ritenuto interessante proporre una ricerca sull’attuale situazione italiana, valutandola alla luce di un confronto con la scena internazionale. Trattandosi di un argomento su cui il dibattito é in progress, ci è sembrato opportuno chiamare direttamente in causa i curatori italiani, attivi sia in campo nazionale che internazionale, invitandoli a riflettere sulla questione ponendo loro alcune domande. Quest’ultime sono qui di seguito pubblicate e le relative risposte figurano articolate in una sintesi composta anche dalle citazioni di alcuni contributi, in parte riportati per sottolineare o contraddire alcuni punti di vista.

continua su

“Non sto lavorando con dei curatori, ho degli Agenti”. Così rispondeva Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev in merito alla sua documenta (la numero 13, che si terrà nell’estate del 2012 a Kassel) durante l’incontro con Marco De Michelis tenutosi presso la Fondazione Ratti lo scorso 27 gennaio.

(Qui la bella recensione su Domus a firma di Francesco Garutti: http://www.domusweb.it/it/art/planting-a-seed-carolyn-christov-bakargiev-alla-fondazione-ratti/)

“In un sistema dell’arte dominato dalle pratiche curatoriali”, dice Christov-Bakargiev, “la mia intenzione è di agire proprio senza un piano curatoriale pre-definito”. Un’entità curatoriale instabile.

Agenti, dunque. Termine di cui si sottolinea l’origine latina e il significato legato al fare. Sono critici, organizzatori e artisti, quali Leeza Ahmady, Ayreen Anastas & Rene Gabri, Sofía Hernández Chong Cuy, Sunjung Kim, Koyo Kouoh, Joasia Krysa, Marta Kuzma, Raimundas Malašauskas, Chus Martínez, Lívia Páldi, Hetti Perkins, Eva Scharrer, Kitty Scott e Andrea Viliani. Ciascuno ha un suo ruolo preciso e a questi si affiancano anche editor e assistenti nonché scienziati, direttori di museo e teorici nel comitato d’onore.

Ma, potremmo chiederci, in cosa un Agente differisce da un Curatore?

Un’altra traccia per ragionare e pensare al ruolo del curatore oggi, nasce dalle parole che Federico Ferrari scrive nello “Spazio Critico”:

“Come scrive Blanchot ne L’espace littéraire, “l’opera è opera solamente quando diviene l’intimità aperta di qualcuno che la scrive e di qualcun altro che la legge: lo spazio violentemente dispiegato dalla contestazione reciproca del potere di dire e del potere di intendere”, del potere di mostrare e del potere di guardare. E’ all’interno di questo spazio che, oltre all’artista e al pubblico, si muovono anche il critico e il curatore. Sono questi i personaggi che compongono la trama del libro. Lo spazio è il luogo dell’azione. L’artista e la sua opera ne sono i protagonisti. Il pubblico è il co-protagonista che partecipa all’intimità esposta dell’arte. Il critico e il curatore sono figuranti alla ricerca di un punto di equilibrio affinchè il monologo solipsistico dell’artista sia scongiurato per mezzo di una relazione aperta tra opera e pubblico”.

Una riflessione da Hans Ulrich Obrist “A Brief History of Curating”.

Come può una persona stare totalmente con l’arte?

Si può fare esperienza dell’arte direttamente in una società che ha prodotto così tanto eloquio e costruito così tante strutture per guidare le spettatore?

“Oh arte da dove arrivi, chi ha dato vita ad una tale stranezza? Per che genere di persone sei fatta: sei per i forsennati, sei per i poveri di cuore, arte per chi è senza anima? Fai parte del fantastico mondo della natura o sei l’invenzione di qualche uomo ambizioso? Provieni da una lunga stirpe di arti? Per questo motivo ogni artista è nato nello stesso modo e noi non ne abbiamo mai visto uno giovane. Diventare artista è rinascere oppure è una condizione della vita?”

Gilbert & George

Le sculture viventi di Gilbert & George, con una buona dose di humor, suggeriscono l’idea che l’arte non necessita di mediazione, dato che l’artista si riferisce ad un’autorità più alta, nessun curatore o museo deve ostacolarlo.

Se la figura moderna del critico d’arte è stata ben riconosciuta fin da Diderot e Baudelaire, la sua vera ragion d’essere rimane largamente indefinita.

-TEN FUNDAMENTAL QUESTIONS OF CURATING –

edited by Jens Hoffmann and published by Mousse

é un progetto che nasce dalla volontà di tracciare le coordinate della pratica curatoriale contemporanea con l’aiuto di dieci curatori.

Dieci curatori e dieci saggi scritti che esamineranno i dieci principali temi della curatela!

http://www.moussemagazine.it/tfq.mm?lang=en